Concluding Thoughts

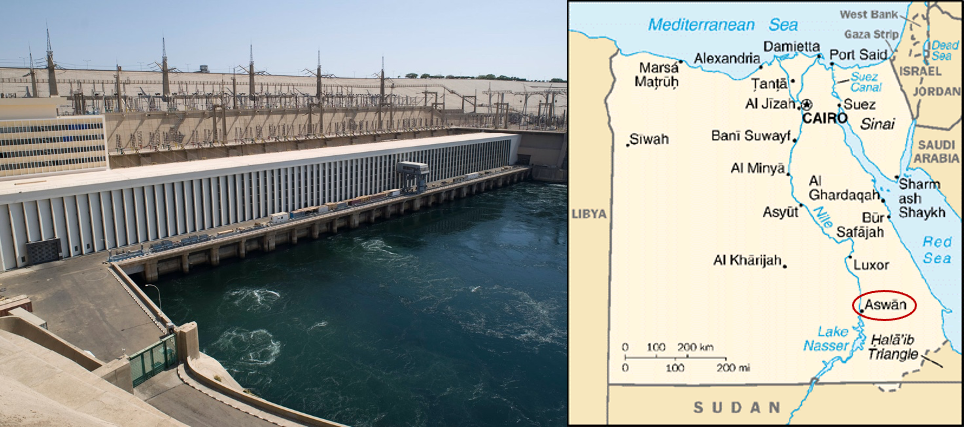

So, we have come to the end of this blog. If there is one take-home message from this series of blogs, it is that Africa's plight is one of distribution, not quantity. The case studies that I explored in this blog such as Ethiopia , Libya , Egypt and Algeria all had a similar situation: water access and subsequently, food production is ample in some areas but not others. For Africa, its limitation has been its climate variability and seasonality. As a result of Africa's physical variabilities, regions like the Sahel and Southern Africa have suffered more than others. In this blog, I explored various solutions for water and food scarcity used across Africa, including water transfer projects , desalination and dams . Although these projects have worked to some degree for their respective users, as a continent characterised with significant poverty levels, expensive engineering solutions will be out of the picture for many African nations. Likewise, the physical geograph